Mandela’s cell on Robben Island

In a grey room with a concrete floor, bars on the windows and fluorescent tube lighting, a group of about 40 tourists is sitting on narrow benches listening to Ntambo Mbatha, a 49-year-old former inmate on Robben Island, explain what life was like in the notorious prison where Nelson Mandela was held during the struggle against apartheid.

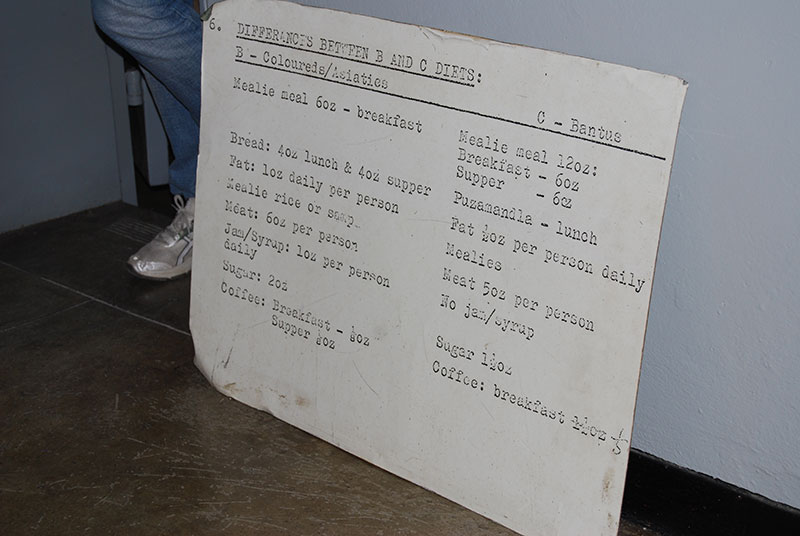

Mbatha has just shown us a dirty mat on which inmates used to sleep and is pacing about as he used to during his seven-year “terrorism” sentence in the 1980s. “When you arrived you were given a number. Your name ceased to exist,” he says. “We lost our identities and were divided on racial grounds: blacks, coloureds and Indians.”

The policies of apartheid were maintained even on this hot dusty island that is only a 45-minute ferry trip from the Cape Town waterfront. “But we refused to be divided,” Mbatha says proudly, leading us through a courtyard full of weeds to the section where Mandela and other political leaders were held in solitary confinement. Mandela spent 18 of his 27 years in captivity on Robben Island. He was released 20 years ago next Thursday.

Mandela’s cell was small and grim — much smaller than the bathroom at my swanky hotel back on the Victoria & Alfred docks in Cape Town. We file past with cameras flashing, taking in the mat on which he slept, a tiny wooden table and a red toilet bucket. “We” consists of a mixed group of overseas tourists and South Africans of all colours. Although there has been chatter as we walk through the courtyard, we fall silent by the grey metal bars.

It is a moving moment. “This is the first time I have been here and it is very sad,” Carolin Sejeng, 38, a black medical co-ordinator from Johannesburg, says in the courtyard afterwards. “Sometimes you just don’t realise what things are like until you see them with your own eyes.”

Tours to Robben Island take about four hours — 45 minutes each way on the ferry, with a walk through the prison compound and a drive around the island on buses bearing the slogan: “The journey’s never long when freedom’s the destination.” The experience comes alive because the guides are former inmates.

Mbatha takes us to a room near the former censor’s office. This was where all letters were read before being passed on to prisoners once a week. Political messages were cut, but the censors also often deleted love messages.

After telling us this, Mbatha regales us with his own story. He left South Africa aged 21, travelling via Swaziland and Mozambique to Angola, where he was trained by the African National Congress, before returning to South Africa, where he was arrested in Soweto for anti-apartheid activities.

He was taken to a detention centre where he was “severely treated both physically and psychologically: I cannot begin to tell you what happened”. As we part, we shake his hand, and he is asked how he can bear to return here. “It is just my work,” he says simply, with a smile.

We file on to a bus, where we meet another guide, Sedick Levy, 68, who was imprisoned on the island in 1963. As we drive to a limestone quarry he tells us about the Sharpeville massacre, in 1960, when at least 69 protesters were shot dead by police in that township.

Levy tells us that work in the quarry was a hard slog and how sunlight hurt the workers’ eyes, but they were refused sunglasses. The toilet at the quarry became an important place where inmates could talk to each other without being overheard. “Some of our youths today think that freedom has fallen from the sky,” he says quietly. “Little do they know how their parents suffered.”

Farther on, we look out across to the splendid silhouette of Table Mountain and Levy says: “I hate this place.” He is referring to Robben Island, not South Africa. He loves his country now: “Before I kick the bucket, at least I can say that I have lived under a democratic government.”

A gift shop near the ferry dock sells copies of the shirt printed with goldfish that Mandela wore when he returned to Robben Island, as well as postcards bearing his messages. “The struggle is my life. I will continue fighting for freedom until the end of my days,” one says, while another, more cheekily, says: “I cannot help it if the ladies take note of me; I am not going to protest.” Chess sets are on sale with pieces made in the shape of F. W. de Klerk, Desmond Tutu and Mandela (the king).

Only 20 years after his release life has changed beyond recognition on this once notorious island.

Need to know

Getting there ITC Classics (01244 355527, itcclassics.co.uk) offers five- night trips staying at Table Bay Hotel (suninternational.com) on the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront from £1,580, flights and transfers included. BA (ba.com) has return flights from £619.

Getting around Holiday Autos (holidayautos.co.uk) has car hire from £118 for a week.

The Robben Island Museum (robben-island.org.za) has four daily ferry departures. Tours are popular, so book well in advance on the internet — you can print out tickets, £17.

Nelson Mandela: for details on 20th-anniversary freedom celebrations, see nelsonmandela.org.

First published in The Times, February 6 2010

Prison yard

Different diets for different races

Sentry tower