On the train from Beijing to Pyongyang (more pictures below)

THE communists were watching intently. One wore a rough, green military uniform with a cut-off collar. He had a large, moon-like face and an inscrutable expression. The other, who had a flint-like look in his eye, was in a slick grey suit.

Both, like almost everyone else I was about to meet in the country, sported red circular badges depicting North Korea’s founding father, the “great leader” Kim Il Sung, who helped defeat the Japanese and set up the country in the 1940s. Their shoes were neatly placed on the floor of my tiny compartment on the Beijing to Pyongyang train. Journey time: 26 hours.

I sat up sharply. I was fully clothed and had been resting while officials took away my passport. This had already taken two hours. I was the only westerner on the shiny green train.

The man in the grey suit asked: “Do you have a mobile phone?” He seemed pleased I did. He took it, examined the casing, placed it in a brown envelope, sealed the ends with tape, stamped a red mark on the front, and said: “Do not use mobile phones in North Korea.”

I was asked to open my bags. The man with the moon-like face asked: “May we smoke?” And without a chance for a reply, they lit up.

Through a fug, they peered at my possessions. “What is this?” snapped the grey suit. It was a book by T.S. Eliot. “Poetry,” I said. He looked suspiciously at the cover. The other man flicked through the Bradt guidebook, examining the pictures and grunting. “And this?” It was a thriller by Lee Child. “Ah, crime action thriller,” he said, as though this was OK.

“Are you married?” asked the grey suit, suddenly. I said I wasn’t. He drew on his cigarette, exhaled a plume of smoke and replied thoughtfully: “A single man may live like a king but die like a dog.”

With that, they handed over my passport and departed. I was in. My visa was in order. I had received free life-counselling. I was a tourist in North Korea – probably the most secretive country on the planet.

Do not expect privacy in North Korea. Tourists are watched carefully by official guides who report to the secret police. I was on a nine-day visit on a package offered by a British travel company (a handful offers trips).

And I was monitored the entire time.

My guides, whose names I won’t give in case I cause them trouble, were with me almost every moment I was not in a hotel room. They met me at Pyongyang’s giant station, and hardly let me out of their sight.

The only time I was allowed to walk “on my own” from my hotel one afternoon, I soon discovered that X had been following.

“You went further than you said you would!” she admonished, in a friendly way. Even though they were keeping a close eye on me – I was visiting as a tourist not as a journalist (few are ever allowed in) – we got to know each other and became chums after their initial bouts of questioning in which I lied and told them vaguely that I was a travel agent. This “interrogation” only ended half-way through the trip, when they ran out of steam.

My tour took in Pyongyang, Kaesong in the south by the Demilitarised Zone, where there is the famous border point where you walk round a negotiating table to step into South Korea, a trip to mountains in the north, and a visit to the West Sea Barrage, a giant structure that prevents floods.

Pyongyang was the highlight. Everything about it was enormous, built on a giant scale: the concrete apartment blocks (many requiring a lick of paint), the endless monuments to Kim Il Sung and the Korean Workers’ Party, the “study houses” where children are taught musical instruments, the building of the Peoples’ Army Circus, the parade squares, the boulevards.

As the guidebook said, it is a showcase city. The country I’d seen from the train looked rundown: crumbling dwellings amid simple farmland with ploughs pulled by miserable-looking oxen with ribs showing.

Pyongyang, however, is designed to impress: there were even chandeliers, marble columns and fancy murals in the subway. It is so markedly different from the rest of the country that non-resident North Koreans are only allowed in with special permits. Otherwise, everyone would try to live in Pyongyang.

But despite the scale of the buildings, it was clear that poverty was a big problem. One obvious sign of the lack of wealth was the almost total absence of cars.

There were hardly any. Often our Landcruiser was the only vehicle on the road. People cycled or walked by, but the giant avenues were empty. This was particularly striking when we drove to Kaesong. Most of the time, we had the ridiculously big ten-lane motorway to ourselves.

Along the sides, people strolled along, staring in disbelief at the westerner – me – driving past.

We visited embroidery factories, acrobatic shows, memorials to soldiers, farms, Buddhist temples (Buddhism is tolerated), and military museums commemorating “victory” over the US in the Korean War in 1953. We stayed at comfortable hotels designed for diplomats; the one in Pyongyang even had CNN as well as the dull local station (constantly showing military band performances), though there was never the chance to use the internet freely.

At one hotel there was a computer where you could send emails from a hotel email account. But this was only allowed after the address of your recipient had been checked. Two of my three emails never arrived.

The cult of Kim Il Sung, who died in 1994 and whose son Kim Jong Il now runs the country (often causing bother over his pursuit of nuclear weapons), is strong.

Whenever we visited monuments to Il Sung – and we also went to his giant mausoleum, where locals broke down in tears – I was made to bow.

Even the slightest joke about the endless pictures of the Kims, which were on virtually every street corner, was frowned upon by the guides. “We do not say things like this about our great leader,” said X.

On Mount Myohyang, we went to the International Friendship Exhibition, a collection of gifts presented to the Kims by a ragbag of figures including Gaddafi, Castro and Mugabe. I asked whether it was ironic to celebrate international friendship when the citizens of North Korea are rarely permitted to visit the outside world.

“That is a very journalistic question,” said X, suspiciously.

Food was varied. We ate lots of barbecues (duck, chicken, beef), rice, tofu, bean sprouts, and kimchi, a spicy cabbage. Occasionally – as a westerner – I was given disgusting burgers and chips.

Sometimes the guides ate with me, other times not. But they always knew where I was, even if I was left alone. “You went to bed early,” X would say, even though I had eaten by myself and gone upstairs without thinking I’d been noticed.

You’re never really alone in North Korea. Big Brother really is always watching… sometimes even, as I discovered on the train from Beijing, when you’re fast sleep.

Traffic warden, Pyongyang

Traditional dress, Pyongyang

Central square, Pyongyang

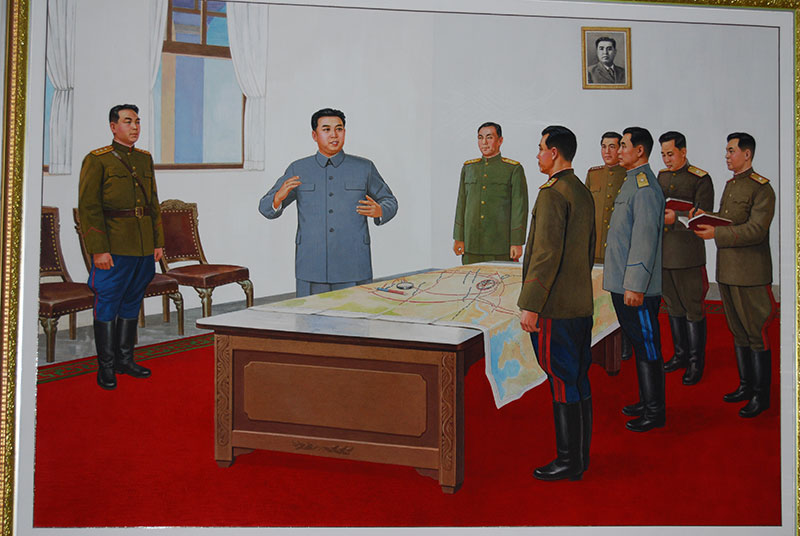

The “great leader” and son – painting in hotel

Parade practice, Pyongyang

Parade practice, Pyongyang

Meeting the service station employees on the way to the DMZ

Centre of Pyongyang

At the DMZ

Propaganda poster

The “great leader”

Propaganda poster

Propaganda poster

Soldiers taking a break

Barbecue picnic

Busker and woman in red

Lining the street to await the Olympic flame

Legs tied together – not sure why…