Not everyone at the end of the 19th century was convinced by the newfangled “self-propelled cars” being built by Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler. After the creation of their first models, in 1886, the German Kaiser Wilhelm II asserted: “I do believe in the horse. The automobile is no more than a transitory phenomenon.”

That quote is engraved in gold on the base of a display featuring a stuffed white horse at the entrance of the multimillion-pound museum devoted to all things Mercedes-Benz, next door to its research, engine development and testing track on the edge of Stuttgart.

“You like the horse, eh?” says Monica Kleinedam, our guide, who is dressed in a charcoal grey suit, orange scarf and white blouse, and looks as if she could be about to make a presentation to a board of directors at a City firm. “That is what one horsepower looks like. Now we are going to see more . . .”

The Mercedes-Benz Museum makes a bold statement. From the outside it looks like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao — a gleaming metallic structure with graceful curves and tinted glass, next to a flyover leading to the city centre.

The proximity to the highway is not coincidental. “The Dutch architects wanted to be by the motorway,” Kleinedam says. “They won the contract for the design because they said, ‘If you are showing cars you should be close to cars’.”

Next to the motorway is the Mercedes-Benz plant. Cars zoom around its test track. Speeding vehicles, including lorries and buses, cling to a curved wall as centrifugal forces and gravity do their bit. But just as impressive as the building is the fantastic collection of Mercedes-Benz cars, the most extensive in the world.

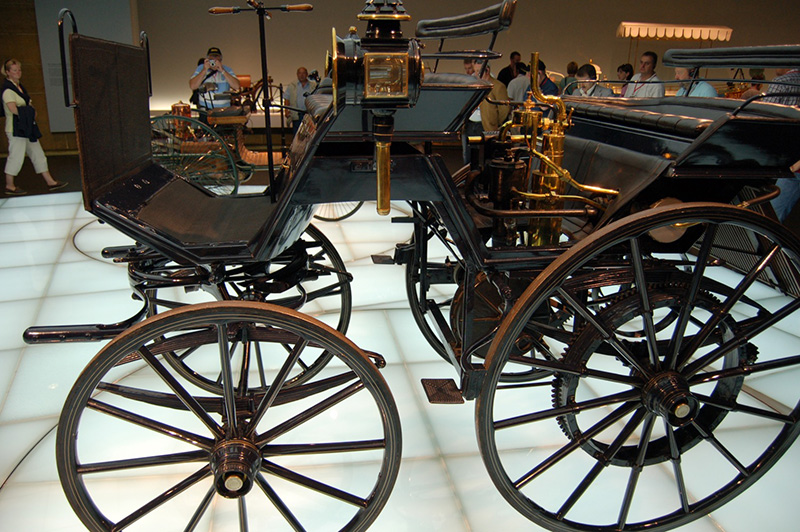

Gottlieb Daimler, a former gunsmith’s apprentice, built the first four-wheel, petrol-powered motor vehicle in 1886. Cumbersome steam-powered road vehicles date back as far as 1769 in France, developed by Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot, but this was a whole new ball game.

Daimler’s vehicle looked like a horse-drawn carriage — without the horse — and had a top speed of 11mph (17km/h). To put that in perspective, the Jamaican sprinter and world record holder Usain Bolt reaches speeds of 27mph during the 100 metres.

In a display unit is the “legendary Grandfather Clock” engine, which developed 650rpm compared with previous limits of about 200. “This is the beginning of driving,” Kleinedam says as she leads us to Karl Benz’s three-wheel version, also created in 1886.

Benz, the son of an engine driver, was, like Daimler, brought up near Stuttgart. He ran a foundry supplying building materials, and began experimenting with engines in the 1870s.

Fans of Top Gear could spend a lot of time in this museum, I soon realise.

As we wind our way around the circular building, we see more rickety-looking early designs, as well as the world’s first petrol-engined fire engine, developed by Benz in 1892, and the first bus, adapted by breweries to carry barrels. “The horses were quite happy with this invention,”Kleinedam jokes.

A display shows early “gentlemen drivers”, who broke with the tradition of chauffeur-driven vehicles and took the wheel themselves.

Most seemed to favour large moustaches, white suits and pith helmets, a dress code that apparently was all the rage around Stuttgart in the late 19th century.

By 1900 the cars were zipping along at 35mph as Daimler led the way with vehicles with radiators at the front that allowed engine parts to cool more efficiently. Soon after, a local businessman began entering races with Daimler cars under the first name of his daughter, Mercedes. They were hugely successful, and “Mercedes” stuck — later becoming Mercedes-Benz when the companies merged in 1926.

As this history develops, the cars get better and better. By the mid-1920s there are gorgeous, red, low-slung sports cars with top speeds of 100mph, limousines with diesel engines in the 1930s, and futuristic, silver, bullet-like cars with plush red leather interiors and flip-up doors in the 1950s.

“They were very interesting if you had a young lady in a short skirt who wanted to get out, ” Kleinedam says.

On display in the museum’s side rooms are early lorries, police cars, Formula One racing cars, vans, taxis and even a “Papa Mobile”, created for Pope John Paul II in 1980. After the 1981 assassination attempt a bulletproof version was produced.

The colours of the 1960s models are glorious: deep oranges, emeralds and ruby reds, all making you wonder why manufactuers are so conservative now with their greys, silvers and blacks.

Kleinedam tells us that seatbelts were patented in 1903 and became compulsory in Germany in 1976 (Britons were made to wear them in front seats in 1983). And we see a series of gleaming racing cars covered in advertisements for Bridgestone, Vodafone, Esso and Mobil.

By this stage there is no doubt: Wilhelm II was definitely wrong. Or perhaps, if the green brigade has its way and restrictions are placed on “carbon criminal” driving, he was right — but just didn’t know why.

Either way, the Jeremy Clarksons of the world will enjoy the Mercedes-Benz Museum.

Need to know

Mercedes-Benz Museum (00 49 711 1730000, www.mercedes-benz.com/museum), Mercedesstrasse 100, Stuttgart. Admission £5.50.

Mo.hotel (00 49 711 280560, www.mo-hotel.de), Hauptstrasse 26, Stuttgart, is owned by DaimlerChrysler and has rooms from £87 a night.

British Airways (www.ba.com) has return flights from Heathrow to Stuttgart from £116.

First published in The Times, June 20 2009

Pictures from the museum