Third Man Museum, Vienna (more pictures at the end of the article)

Under a sycamore tree on a corner of a road just south of the Vienna opera house a handful of tourists has gathered by a hole in a pavement with a spiral staircase leading down into darkness.

“This is the real location: the one you see in the movie!” exclaims Gerhard Strassgschwandtner, our guide to the sites from The Third Man, written by Graham Greene, which won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival 60 years ago this week.

As a tram creaks towards the golden dome of the Secession building, we descend the damp steps down which Harry Lime, played by Orson Welles, fled the authorities chasing him for operating a watered-down penicillin racket during the postwar years — a time when Vienna was a divided city under the control of the Russians, Americans, British and French.

Greene, who entered the Viennese sewers here during filming in 1948, had been inspired to write the story after hearing about the deaths of children treated with diluted penicillin, much of this told to him by his friend the Times correspondent Peter Smollett.

Strassgschwandtner leads us along passages with filthy puddles to an opening with a murky olive river flowing through a tunnel. We stop at a section in which images of Welles disappearing round a corner, pursued by Joseph Cotten, playing the character Holly Martins, seem to flash up like ghosts.

Greene’s description feels spot-on: “What a strange world unknown to most of us lies under our feet: we live above a cavernous land of waterfalls and rushing rivers, where tides ebb and flow as in the world above.”

This is a real sewer and the smell in places is terrible. Looking down the hellish tunnel in which Lime eventually meets his maker, Strassgschwandtner tells us that many locals do not like the film because they do not want to be reminded of the poverty and destruction in the city after the war.

For Strassgschwandtner, however, who is in his early fifties and owns and runs the Third Man Museum, the film opened up a period of his country’s history that he had not been taught properly at school. He believes that too many Austrians consider the Second World War to be a German war that was nothing to do with them. When he was growing up he was not even taught the history of the war at high school.

The Third Man helped him to understand Austria’s involvement and what happened to Vienna in the aftermath: that it was controlled by foreign powers. The star of the film is not Welles, he says: “It is Vienna.”

Out in the open again, thankfully, we visit Max Joseph Platz, where Lime faked his death to try to fool the authorities. Again, there is the spooky sensation of seeing characters from the film: it was here that a young boy wearing a cap looks suspiciously at Martins, an outsider, and draws a mob’s attention to him.

They chase him across the cobbles, past the distinctive entrance of a building with four columns in the shape of maidens, around a corner and out of the square.

We visit the spot where Martins first lays eyes on Lime: a key moment, when Welles, with his impassive moon-like face, first appears on screen, on a street not far from Sigmund Freud Park. We visit Am Hof square, where Lime disappears as though into thin air behind an advertising hoarding that conceals a doorway entrance to the sewers.

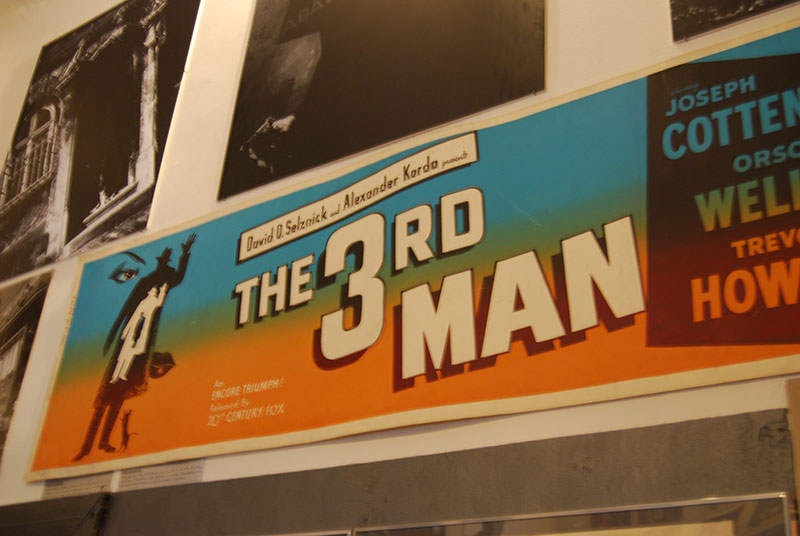

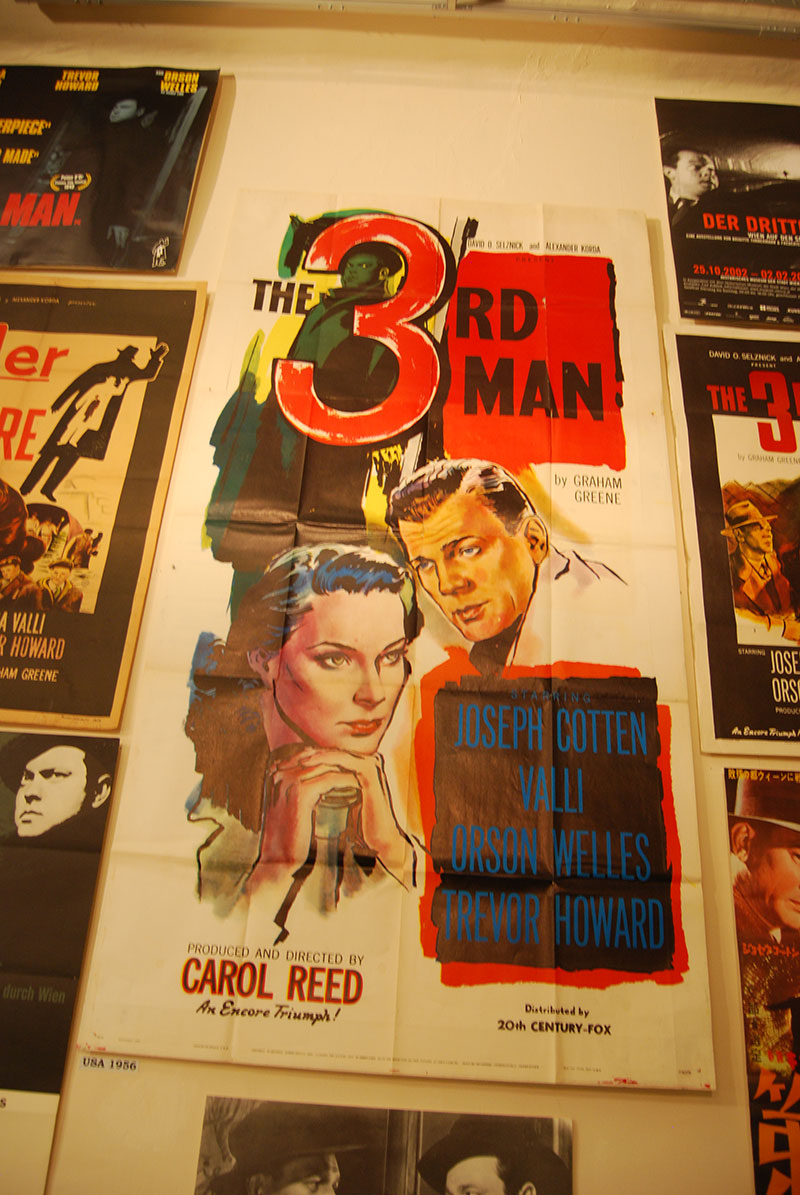

And then we take in the Third Man Museum, which is close to Naschmarkt, a seedy centre of black market trade and prostitution when Greene visited but now bustling with trendy caf?s and smart fruit and veg stalls. The museum opened three years ago and it contains an Aladdin’s cave of film paraphernalia, with displays that include the original Austrian zither used to play Anton Karas’s catchy, hypnotic soundtrack, first editions of the novella, and black-and-white shots of the cast.

There is also a two-minute clip using an old-fashioned cinema reel, although the whole film is also shown three times a week, mainly for tourists, at a full-screen cinema in the Old Town — a testament to its enduring appeal.

Greene stayed at Hotel Sacher, where British military staff lived and where Welles and the rest of the crew also put themselves up in 1948. The hotel is repeatedly mentioned in the novella, and it is where Martins stays after bluffing his way to a free room by pretending to be a famous author when he arrives in Vienna at the beginning of the film.

It’s an ornate jewellery box of a place, with gilded antique furniture, plush red velvet furnishings, oriental vases, front doormen in top hats and tails, and a guest list that includes all sorts of film stars (Sharon Stone and Emma Thompson recently), politicians (Gerhard Schr?der, the former German Chancellor, staying on our visit) and dignitaries (the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh came in 1969).

There’s a Third Man suite in the room in which Greene is believed to have slept, filled with stills from the film and a shot of Welles with a handwritten note from him praising the hotel’s bar for serving “the best bloody mary in the world”. Downstairs, we make our way to the small, cosy Blue Bar, where the author and Welles enjoyed many a drink.

An American who might pass for a senator is asked by a waiter what gin he would like in his G&T. We sit in a corner and watch the waiters glide by serving cocktails, just as they must have done in the 1940s.

Afterwards, as a final homage, we take the subway to Prater Park for a trip on its iconic Ferris wheel. The old-fashioned red compartments in which Greene took a ride during his research (when this was part of the city’s Russian sector) look exactly as they did in the film’s most famous scene, when Lime pontificates on the rights and wrongs of his penicillin racket, pointing at the “dots” of people in the funfair far below:

“Would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving — for ever? If I said you could have £20,000 for every dot that stops, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money — without hesitation?” It may be 60 years later, but the ghosts of Greene live on in Vienna.

Need to know

Getting there Kirker Holidays (020-7593 2283, www.kirkerholidays.com) offers a three-night B&B break staying at the five-star Hotel Sacher from £970pp, including return scheduled flights and private car transfers. Cheaper hotel options are available through the Austrian National Tourist Office (0845 1011818, www.austria.info). EasyJet (www.easyjet.com) has returns from Stansted to Vienna from £40.

Graham Greene’s Vienna “In the Footsteps of the Third Man” tours (www.viennawalks.com) are run every Monday and Friday at 4pm, meeting at the U4 Station Stadtpark metro station at the Johannesgasse exit. They last 2hr 30min and cost £14.50.

The Third Man Museum (www.3mpc.net), 25 Pressgasse, is open 2-6pm on Saturdays. Entrance £6.

The Third Man is shown in English at the Burg Kino cinema (www.burgkino.at), 19 Opernring, at 10.55pm on Fridays, 2.15pm on Sundays and 5.40pm on Tuesdays — but check beforehand as times sometimes alter slightly.

More journeys in Greeneland

The Comedians The Oloffson, Port-au-Prince, Haiti The basis of the Hotel Trianon in Greene’s 1966 novel The Comedians, set during the rule of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. The main character is the hotel’s owner, who discovers a body in the pool: “My first thoughts were selfish ones: you cannot be blamed if a man kills himself in your swimming pool.”

Doubles from £53; http://hoteloloffson.com Our Man in Havana The Nacional, Havana, Cuba When Mr Wormwold, the vacuum salesman hero of Our Man in Havana, is told that he is about to be poisoned at a meal at the Nacional, other guests overhear the warning:

“One of them, an American, said, ‘Is the food that bad?’ and everyone laughed.” Doubles from £123; www.hotelnacionaldecuba.com The Quiet American The Majestic and the Continental, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam The Majestic and the Continental feature in The Quiet American, first published in 1955.

Thomas Fowler, the protagonist, sits at the Continental’s bar: “It was the early evening . . . the dice rattled on the tables where the French were playing Quatre-Vingt-et-Un, and the girls in white silk trousers bicycled home down the rue Catinat.”

Doubles from £97 at the Majestic (www.majestic saigon.com) and from £40 at the Continental (www.continental-saigon.com)

First published in The Times, September 5 2009

Inside the Third Man Museum

Old film poster

View from Hotel Sacher

Inside Hotel Sacher