As Paul Theroux nears the South African border with Namibia in his engaging travelogue The Last Train to Zona Verde (Hamish Hamilton, £20 £15; e-book £11.99), he contemplates why a person “way past retirement age and alone” should be putting himself through the stresses and strains of independent travel in Africa. The landscape is parched, with bald hills and scrub. “What perverse aspect of my personality was I indulging?” he asks. It is the type of question he regularly raises on this journey from Cape Town to Luanda, the capital of Angola, which includes a chapter entitled: What Am I Doing Here?

As Paul Theroux nears the South African border with Namibia in his engaging travelogue The Last Train to Zona Verde (Hamish Hamilton, £20 £15; e-book £11.99), he contemplates why a person “way past retirement age and alone” should be putting himself through the stresses and strains of independent travel in Africa. The landscape is parched, with bald hills and scrub. “What perverse aspect of my personality was I indulging?” he asks. It is the type of question he regularly raises on this journey from Cape Town to Luanda, the capital of Angola, which includes a chapter entitled: What Am I Doing Here?

His answer is that “physical experience is the only true reality. I didn’t want to be told about this, nor did I wish to read about this at second hand. I didn’t want to look at pictures or study it on a small computer screen … I wanted to be travelling in the middle of it.”

This spirit of wanderlust permeates the book as he visits shocking shanty towns, catches dusty buses across desolate terrain, meets Ju/’hoansi people (who have a claim to be the living remnant of the first humans on Earth), tussles with Angolan border officials, has his credit card copied (and $48,000 — £32,000 — stolen, he later finds), and investigates the zona verde (green zone) of Angola, where the country’s last few wild animals live.

Despite the title, Theroux does not in the end take the “last train” (he sticks to bumpy buses and four-wheel drives). But, in Italian Ways: On and Off the Rails From Milan to Palermo (Harvill Secker, £16.99 £13.99; e-book £9.99), Tim Parks spends the whole time scooting about on the ferrovie (“ironways”).

Parks, who has lived in Italy for more than 30 years and written often about the country, casts a wry eye on officialdom and the characters he meets on the “train of the living dead” that he catches from his home in Verona to his job as a professor at a university in Milan. The tale is warmly told, with flashes of humour during encounters with ticket inspectors, frustration about the furbo (“sly ones” who jump queues), and an appreciation of the low fares that help Italians on low wages get about.

Robert Twigger’s wide-ranging Red Nile: A Biography of the World’s Greatest River (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £25 £20; e-book £12.99) examines another way of moving around. The Nile has attracted adventurers since ancient times, and Twigger heads for the source of the river while reflecting that “crocodiles are the biggest animal killers in Africa”, annually claiming more than 1,000 lives. He sometimes takes to a kayak, safe in the knowledge that if he’s chased by a hippo he can outpace his attacker as the creatures can reach speeds of only 5mph. The history of the river and the countries it passes through is interwoven with many interesting snippets — for example, that the Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat said that the “attractive lines of the slim-fit uniform would be spoilt by wearing a bullet-proof vest” on the day he was assassinated.

The Robber of Memories: A Journey Through Colombia by Michael Jacobs (Granta, £9.99 £9.49; e-book £16.99) is a fascinating vignette, describing a journey to the source of River Magdalena. It sprang from a chance encounter with the Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez, who went on a journey down the river as an impressionable 15-year-old and tells him: “I remember everything about the river, absolutely everything.” Jacobs is soon off, taking barges to out-of-the-way towns, dodging rainforest guerrillas (he is lucky to survive one encounter), and all the while reflecting on his mother’s terrible struggle with dementia.

Escaping to think about life is also the theme of Sylvain Tesson’s concise and brief Consolations of the Forest: Alone in a Cabin in the Middle Taiga (Allen Lane, £16.99 £13.99; e-book £10). About to turn 40, the French travel writer decided to live as a hermit in a log cabin on the shores of Lake Baikal in Siberia for six months. He’s no Robinson Crusoe, amusingly listing his “requisite supplies”, which include snowshoes, solar panels, kayaks, vodka, cigars (plus a Tupperware “humidor”) and bottles of Tabasco sauce. He also takes a library of 70 books, including Daniel Defoe’s classic.

Tesson drinks a lot, catches the odd fish, skates, smokes his cigars, breaks up with his girlfriend by satellite phone and bemoans the state of modern life (a little pretentiously, perhaps).

Sara Wheeler’s O My America! Second Acts in a New World (Jonathan Cape, £20 £14.99; e-book £19.81) is another journey of discovery. As she approaches the age of 50, Wheeler admits that she is “going through a gloomy phase” with “my children needing me less, me needing them more”. This offbeat, intriguing book follows the adventures of six remarkable women in “turbulent midlife” who took off to the United States in the 19th century. One of these is Fanny Trollope, the mother of Anthony, who created a stir by publishing Domestic Manners of the Americans on her return to Britain. It upset New Yorkers, who created effigies of her as a goblin.

Three paperbacks about walking stand out. The first is Robert Macfarlane’s The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot (Penguin, £9.99 £9.49; e-book £5.99), a philosophical contemplation of the nature of walking with a focus on ancient tracks, partly inspired by the travel writing of the poet Edward Thomas. Meanwhile, Hugh Thomson’s The Green Road into the Trees: A Walk Through England (Windmill, £9.99 £9.49; e-book £7.49) is a more straightforward account of travelling along many of the same pathways; gently told, with rich humour and an enjoyable sense of inquiry. Sinclair McKay’s Ramble On: The Story of Our Love For Walking Britain (Fourth Estate, £8.99 £8.54; e-book £14.39) acts as a biography of Britain’s favourite outdoor pursuit, dwelling on our love of taking to the countryside, while covering disputes between landowners and ramblers, and asserting: “The only way to understand a land is to walk it.”

Finally, for a bit of fun, An Englishman Abroad: Discovering France in a Rowing Boat by Charles Timoney (Particular, £16.99 £13.49; e-book £9.99) tells the story of making a bet on New Year’s Eve that he could travel from the source of the Seine to the sea by rowing boat — and then doing it. Timoney, who has built a 7ft boat, pushes off, wondering like Theroux where he’s heading and why, with perennially soggy jeans and encounters with the river police lying ahead.

Blue Dahlia, Black Gold: A Journey Into Angola by Daniel Metcalfe

August, 2013

On arriving in Angola, Daniel Metcalfe sets himself a goal: “To avoid going bankrupt within a week.” Despite widespread poverty in much of the southwest African country, where memories of the bloody civil war that ended in 2002 are fresh, the recent plundering of oil reserves had created a small band of the (incredibly) super rich.

On arriving in Angola, Daniel Metcalfe sets himself a goal: “To avoid going bankrupt within a week.” Despite widespread poverty in much of the southwest African country, where memories of the bloody civil war that ended in 2002 are fresh, the recent plundering of oil reserves had created a small band of the (incredibly) super rich.

The result was hamburgers for £30 and “awful hotel rooms” for £300 in Luanda, the capital, while the majority of people elsewhere struggled to get by, many turning to the local beer, Cuca, to blot out reality.

This dichotomy poses an “irresistible challenge” to Metcalfe, a journalist and author of a previous travel book about Iran and Central Asia. He is fascinated by what he describes as “reverse neocolonialism”, with the newly oil-rich going on lavish shopping sprees in Portugal. They have already bought up 4 per cent of the companies listed on the former colonialists’ stock exchange.

Angola was the earliest African country to be colonised by a European power and when the Portuguese finally left in 1975 it sparked the civil war in which more than half a million people died.

Metcalfe’s idea is to explore Angola by road to get under the skin of a nation in which corruption and nepotism are rife (the president’s daughter happens to be Africa’s first female billionaire). He is warned by his first contact that he “will get robbed at knifepoint” (he avoids this fate), and is lucky not to lose his rucksack on his inbound flight. Reflecting that he would rather not catch rampant falciparum malaria — the worst version of the disease — and aware that Angola is “an anti-tourism destination”, he pushes onwards.

This sense of living on the edge acts as the drive of the narrative. The book comes soon after the release of Paul Theroux’s The Last Train To Zona Verde, the story of a journey from South Africa through Namibia into Angola, where the sometimes grumpy travel writer is so depressed by the poverty and dangers that he drops plans to travel farther up the west coast of Africa.

Hair-raisingly at times, particularly when taking candongueiro (collective taxis) steered by mad, sometimes inebriated drivers, Metcalfe keeps going. Even when buses almost flip over, or he is forced by police to pay “fines” , he does not do a Theroux and throw in the towel.

Along the way, Metcalfe cleverly weaves in Angola’s colonial history, civil war and rapid rise of the nouveau riche. The “blue dahlia” of the title, slightly obtusely, comes from the “blocks” of the Atlantic assigned to oil companies, one of which is named after the locally much-loved pink dahlia flowers.

Metcalfe meets tribal leaders, including King Carlos Manuel Muatchissengue Watembo of Lunda Tchokwe Territory (who demands that he pay for his beer), dodges tsetse flies, visits shanty towns, and tells the intriguing story of the 17th-century Queen Njinga Mbande, who forced her husband and 50 “male companions” to wear women’s clothing, while she wore men’s and occasionally sacrificed the most handsome male she could find for luck.

Details of the civil war tend to get long-winded, the last couple of chapters feel a touch sketchy (as though the book was rushed to coincide with Theroux’s), and this is not for armchair travellers. Angola’s extraordinary cocktail of corruption, oil wealth, destitution and post-colonial blues adds an altogether grittier, dimension.

Blue Dahlia, Black Gold: A Journey Into Angola by Daniel Metcalfe, Hutchinson, 368pp, £20; e-book £11.99. To buy this book for £16, visit thetimes.co.uk/bookshop

Cities Are Good For You by Leo Hollis

April, 2013

Henry Ford once said: “We shall solve the city by leaving the city. Get people into the countryside, get them into communities where a man knows his neighbours.” Dante was thinking of Renaissance Florence when he wrote of Hell. Jean-Jacques Rousseau considered the city “a pit where almost the whole nation will lose its manners, its laws, its courage and its freedom”.

Henry Ford once said: “We shall solve the city by leaving the city. Get people into the countryside, get them into communities where a man knows his neighbours.” Dante was thinking of Renaissance Florence when he wrote of Hell. Jean-Jacques Rousseau considered the city “a pit where almost the whole nation will lose its manners, its laws, its courage and its freedom”.

In short, cities have long had a pretty bad press. In Cities Are Good For You Leo Hollis aims to set the record straight on the places where more than half the world’s population now lives.

He does so with gusto, attacking the “grumbles of the sceptical and the stuck-in-the-mud naysayers” who complain about life in the Big Smoke, and calling on people to “think again about the city, before it is too late”. Hollis believes it is easy to sigh about gridlock, crowded trains, smog, crime and high-rises — and give up hope that cities can ever be more than concrete nightmares, growing at an alarming rate across the globe. By 2050, 75 per cent of people will be city-dwellers. But throwing up our hands is not the way forward, says Hollis, who was born in London and lives 15 minutes by train from St Pancras with a “view of urban sprawl in all directions”. Instead, he explains, cities must be “reconstructed from the bottom up, not projected from the imagination of a grand wizard planner”. He is particularly critical of the Swiss architect Le Corbusier, whose ideas about functional cities with people slotted into “house-machines” were so influential in the early 20th century.

To make his underlying point — about thinking of cities in terms of people, not grand schemes — Hollis hits the road. He travels to fast-growing Mumbai, where he takes in the world’s most expensive house, the 27-storey, $1 billion home of a leading businessman ; with living spaces for 60 servants, parking for 160 cars and three helipads. He is damning of the growth of the global super-rich, pointing out that 90 per cent of the world’s wealth belongs to the richest 1 per cent. Increasingly unequal societies breed mistrust, Hollis believes, with those at the bottom feeling hopeless. “Inequality undermines the sense of common purpose and ownership, it attacks optimism and a sense of being in control of one’s fate,” he writes. Nowhere is inequality greater than in cities, he says, with the richest 10 per cent in London having 273 times more wealth than the bottom 10 per cent. For cities to work effectively, he argues, there needs to be a more level playing field. In Mumbai, Hollis goes on to visit the very poorest inhabitants in the city’s vast slums, where he slightly vaguely concludes that “improvements from within” rather than bulldozers are the way forward: keep City Hall bigwigs out of it.

His travels also take him to Manhattan’s High Line Park, where a derelict elevated railway line has been turned into green space. Simple schemes like this, dreamt up locally, can humanise a neighbourhood, he believes.

Cities Are Good For You is an intriguing book with a clutter of ideas, but behind them is Hollis’s positive belief that “the complexity of the city offers more chances of making connections than anywhere else”. Living in a city, loneliness is less likely, he argues, and if the world is increasingly going to live in them, it makes sense to think about them more.

Tom Chesshyre’s A Tourist in the Arab Spring has just been published by Brandt.

Cities Are Good For You by Leo Hollis Bloomsbury £16.99. To order for £13.99 including postage visit click here or call 0845 2712134

2011’s best travel books

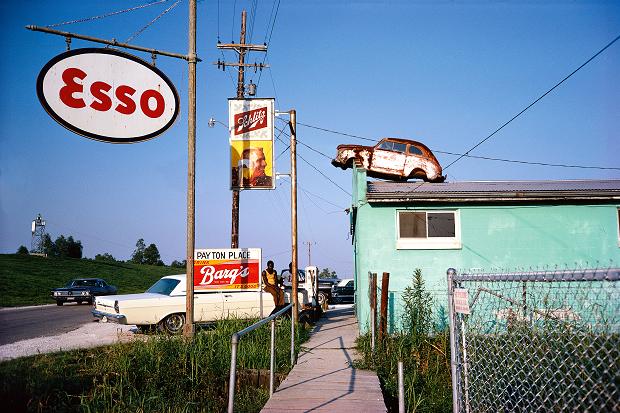

A Memphis scene from photographer William Eggleston’s previously unseen work in Chromes (Steidl, 3 volumes, £200)

December, 2011

In the preface to Paul Theroux’s The Tao of Travel (Penguin, £16.99), the veteran American travel writer ruminates on the human desire to explore foreign lands and refers to The Importance of Elsewhere — a Philip Larkin poem in which Larkin writes that “strangeness makes sense”. Theroux explains that his desire to travel has stemmed from seeking strangeness and wanting “to find a new self in a distant place”.

And he goes on to refute the notion that the internet has created an omniscience that makes the physical effort of travel pointless. There are still plenty of little-known spots left to discover, he believes.

The book has idiosyncratic tips aplenty: take a shortwave radio, advises Theroux, read a novel that is not about the place you are visiting and turn off your mobile phone. But it also acts as an inspiring manifesto to get out and see the world, drawing on the words and wisdom of writers as diverse as Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, Samuel Johnson and Freya Stark — who once wrote: “Travel does what good novelists also do to the life of everyday, placing it like a picture in a frame or a gem in its setting, so that the intrinsic qualities are made more clear.”

This is just what Colin Thubron achieves in his punchy, evocative and short book about visiting Mount Kailas, the most sacred of the world’s mountains, in To a Mountain in Tibet (Chatto & Windus, £14.99). Nobody has ever climbed to the peak of Kailas — it is so treacherous at the top (21,778ft) that some believe it will never be conquered — but many thousands of Buddhist and Hindu pilgrims visit to walk clockwise around its sacrosanct slopes, which is said to purify the soul.

It is a dangerous journey up to 18,000ft, where Thubron, who is mourning his mother, is hit by altitude weariness and becomes temporarily delirious. He lights an incense stick, stretches out some prayer flags and makes his way back down.

During the journey, Buddhist belief is explained, the stifling effect of Chinese control analysed and scenes are captured with poetic precision. “Ropes of glittering light” illuminate wooded valleys and “flocks of butterflies blow like confetti over the stones” by riverbanks.

There is poetry of a different type too in Edgelands: Journeys into England’s True Wilderness (Jonathan Cape, £11.69), by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts. This has to be the year’s most unusual travel book in that it dissects England by birdspotting at sewage farms, day-tripping to landfill sites, hunting down favourite electricity pylons, hanging out in service stations and delighting in a night spent at the Premier Inn Swindon West.

These are, they declare, “complicated, unexamined places that thrive on disregard, if only we could put aside our nostalgia for places we have never really known and see them afresh”.

John Julius Norwich has elements of edgelands in A History of England in 100 Places from Stonehenge to the Gherkin (John Murray, £22.50), even finding room for a service station of his own, the one at the Watford Gap, in his list — which he sees as being somehow symbolic of the spread of motorways across the country. It’s an intriguing book to dip into, with an accessible style and lots of titbits from Emperor Hadrian’s unusual beard to the little-known Huguenot origins of London’s Brick Lane Mosque.

A couple of other historically based travel books stand out. The Lost Photographs of Captain Scott by David M. Wilson (Little Brown, £27), which shows the long-lost pictures that Scott took during his doomed trip to the South Pole. The pictures were overlooked for so long because of uncertainties over copyright. Somehow, however, they have re-emerged — and they are wonderful, capturing not just the desolate scenery but also the gruelling drudgery of hauling sledges through the slush.

The other is Tim Jeal’s comprehensive and lucid Explorers of the Nile (Faber, £20), which describes the Victorian exploits of Richard Burton, John Hanning Speke, David Livingstone, Henry Morton Stanley and others as they sought the source of the mighty river. There are high jinks, close encounters with spears, terrible flesh-eating ulcers — and a terrific sense of the adventure and strangeness that Theroux loves so much.

Beg, Borrow, Steal by Michael Greenberg

February 12, 2011

Working as a waiter at a burger joint, he was sacked for smoking with a “threatening demeanor” (of which he had been totally unaware) during breaks. Driving a taxi, he was held up by a passenger with a gun (“I rolled to the next red light, jumped out of the cab and ran off”). Sorting mail on the graveyard shift at a post office near Grand Central Station, then peddling eye pencil and lip gloss on street corners in the Bronx (when his stock and cash was stolen by teenagers) . . . you could say that Michael Greenberg has had his fair share of jobs and mishaps. This very humorous memoir describes his life as a writer struggling to get by in New York City. In 44 chapters of between 1,100 and 1,200 words, which first appeared as columns in the Times Literary Supplement, he tells it how it is in a series of keenly observed descriptions of what it’s like to live by his pen and his wits in the Big Apple.

Working as a waiter at a burger joint, he was sacked for smoking with a “threatening demeanor” (of which he had been totally unaware) during breaks. Driving a taxi, he was held up by a passenger with a gun (“I rolled to the next red light, jumped out of the cab and ran off”). Sorting mail on the graveyard shift at a post office near Grand Central Station, then peddling eye pencil and lip gloss on street corners in the Bronx (when his stock and cash was stolen by teenagers) . . . you could say that Michael Greenberg has had his fair share of jobs and mishaps. This very humorous memoir describes his life as a writer struggling to get by in New York City. In 44 chapters of between 1,100 and 1,200 words, which first appeared as columns in the Times Literary Supplement, he tells it how it is in a series of keenly observed descriptions of what it’s like to live by his pen and his wits in the Big Apple.

Between his “exhausting progression of dead-end jobs”, which he first takes on because he prefers work in which “loyalty to employers wasn’t required, allowing the illusion of independence that seemed of paramount importance”, Greenberg scores the occasional, often totally ill-suited, assignment. One of these involves writing a script about golf for a cable TV programme enititled The Game that Defined a Century. He gives it his best shot, despite never having played the game: “Golf. Simple. Majestic. Timeless. Imagine a rabbit hole in the wild Scottish grass. Striking a stone with his stick, a solitary walker aims for the hole.”

His first novel fails, curing Greenberg of “any illusions I’d had about the glories of self-expression”. A film about a dentist, for which he has written the screenplay, is humiliatingly panned.

If Greenberg, born in 1952, seems to wear a homing device for street con-artists, he also suffers tribulations with animals (unruly pets), children (the four-year-old son from his second marriage has him “following him around like an anxious valet”) and on one funny occasion he encounters an Anarcho-Marxist transvestite. His writing finally gains widespread recognition after the publication of a memoir recounting his daughter’s manic breakdown (told in Hurry Down Sunshine). He writes of this with a human touch. Beg, Borrow, Steal is full of colour and New York life — downtrodden, unexpected, sometimes uplifting and always real.

Beg, Borrow, Steal: A Writer’s Life by Michael Greenberg Bloomsbury, 240pp, £8.99. To buy this book for £8.54 visit thetimes.co.uk/bookshop or call 0845 2712134

The Magnetic North by Sara Wheeler

November, 2010

With oil speculators moving in, nations squabbling over drilling rights (Russians even planting titanium flags deep on sea floors) and global warming threatening to destroy ways of life of indigenous populations already in the throes of cultural upheaval caused by outsiders, Wheeler sets off on a counterclockwise journey around the Arctic to report what she sees.

With oil speculators moving in, nations squabbling over drilling rights (Russians even planting titanium flags deep on sea floors) and global warming threatening to destroy ways of life of indigenous populations already in the throes of cultural upheaval caused by outsiders, Wheeler sets off on a counterclockwise journey around the Arctic to report what she sees.

Wheeler, a veteran scribbler on chilly parts — she has written about journeys in Antarctica and of the life of the explorer Apsley Cherry-Garrard — travels with an open mind and a clear love of the open scenery. She has a close shave with a polar bear in Canada, is given a giant walrus penis bone in the freezing badlands of Asian Russia (where she sees President Medvedev arriving by chopper on an oil fact-finding mission) and is propositioned by a drunken gold panner in Alaska.

The brilliance of the book, based upon on-and-off visits over two years, comes from the feeling of visiting the front line of perhaps the biggest issue of the day: climate change and the world we are leaving for future generations. Scientists crop up along the way, most with sad statistics to relate. With melting ice and pollutants hitting Arctic lifestyles hard, Wheeler wryly comments on the paradox of a people who would have preferred to have been left well alone. The keenly observed result is sharp, colourful and powerful.

The Housekeeper and The Professor by Yoko Ogawa

July, 2010

This short novel, more like an extended short story, about the beauty of numbers felt like one big, strangely lovely, mathematical equation. Take a brilliant, ageing maths professor whose memory lasts just 80 minutes because he has been in a car crash, add a young housekeeper whose necessarily hard-working existence (she is a single mother caring for a ten-year-old son) means that she is devoid of an inner life, often arriving home late to her “latch key” boy, and see what happens.

This short novel, more like an extended short story, about the beauty of numbers felt like one big, strangely lovely, mathematical equation. Take a brilliant, ageing maths professor whose memory lasts just 80 minutes because he has been in a car crash, add a young housekeeper whose necessarily hard-working existence (she is a single mother caring for a ten-year-old son) means that she is devoid of an inner life, often arriving home late to her “latch key” boy, and see what happens.

The title design itself hints at this using the plus sign in The Housekeeper + The Professor. Ogawa examines this highly unusual relationship, in which the professor begins to reveal the secrets of amicable, perfect, deficient and abundant numbers (among much else) to his keen-to-learn housekeeper, showing that mathematics is not as dull and complicated as many people like to make out, often going blank at the very thought of adding up a list of figures.

It works, but the book is, as Bronwen Maddox points out, a conceit. The plot is unrealistic: would such a set-up ever happen? The protagonists, apart from the housekeeper’s son Root, feel almost as though they exist in a void. She comes to work each day and the professor reveals another intriguing maths secret — usually asking her a simple question, such as her date of birth, and then using her answer to play with the numbers.

I felt as though Ogawa was trying to show that the sureness of mathematics can provide relief in an otherwise complicated world. The housekeeper has a tough life, but numbers seem to come to her rescue. It made me think of all those people I see playing Su Doku, a game popularised in the same country.

The plot moves gently along (maybe a little too gently, as Damian Whitworth observed). The professor says that “explaining why a formula is beautiful is like trying to explain why the stars are beautiful” and Ogawa has cast her spell so well that I was inclined to believe it — although at times the “miracle” of numbers is over-egged, as when the housekeeper declares: “A light was shining at the end, leading me on, and I knew it was the path to enlightenment.”

There is a comic side to the story, with the professor wearing a mad jacket covered in Post-it notes with little reminders of who he is and what he does — so that he can remember as much as possible. I loved the well-observed trip to a baseball ground (a sport obsessed with statistics) and the neat way in which the housekeeper’s son, also infected by the numbers bug, goes on to teach mathematics at a school. It is a charming, slight and well-told story.

All Gone To Look For America by Peter Millar

June, 2010

Railways in the United States have long been connected to the country’s sense of nationhood — in a way they simply are not in the UK. When the Golden Spike, completing the final link in the first coast-to-coast railway line, was tapped into place in Utah in May 1869, it was an important symbolic moment for the fledgeling state.

Railways in the United States have long been connected to the country’s sense of nationhood — in a way they simply are not in the UK. When the Golden Spike, completing the final link in the first coast-to-coast railway line, was tapped into place in Utah in May 1869, it was an important symbolic moment for the fledgeling state.

The feeling that America truly existed from “sea to shining sea” was made real by the two lines of metal laid out across the vast continent: the Wild West, after all the shoot-outs, was finally won by a railway man.

A couple of years ago — with George “Dubya” Bush still in power — Peter Millar set out to explore the vast network of train lines that now criss-crosses the US. Travelling from New York via Chicago, Seattle and Los Angeles, and then back via Texas, New Orleans, Memphis and Washington DC on Amtrak trains, Millar offers a snapshot of a country on the cusp of change (the journey takes place shortly before Obama’s election victory).

He does not attempt to be “definitive”, saying as he leaves for New York that he will be “opinionated, muddle-headed maybe, but always honest” — and that he’ll enjoy a beer or two along the way.

He certainly achieves the latter — visiting the country’s many new microbreweries and sampling their wares, while avoiding “insipid, pale, and tasteless” American low-calorie beers, is a big part of his journey.

The result is a lighthearted month-long romp around iconic US sights such as Niagara Falls, the Grand Canyon, the first Starbucks (in Seattle), Bing Crosby’s old home in Spokane in Washington, Hollywood and Graceland, with bumpy rides in between (Amtrak trains never exceed 79mph partly because of the sometimes uneven tracks) and plenty of bar-room chat thrown in.

Millar explains how the arrival of the motor car brought an end to the glamour era of railways, but suggests that those days could be about to return as more people worry about greener travel. This fun, quirky, and often boozy, book shows you how to do it.

All Gone to Look for America: Riding the Iron Horse Across a Continent (and Back) by Peter Millar (Arcadia, £8.99, 319pp)

Hackney, that Rose-Red Empire by Iain Sinclair

February, 2010

Iain Sinclair begins this peculiar travel book-cum-memoir having been struck on the head by an egg thrown by a gang of young “car-jackers”. He explains that the gang normally aims at car windscreens: drivers who give chase often find radios or mobiles missing later. So much so normal in Hackney, Sinclair concludes, as he wipes the yolk out of his hair and reflects on life in the borough that has been his home for more than 30 years.

Iain Sinclair begins this peculiar travel book-cum-memoir having been struck on the head by an egg thrown by a gang of young “car-jackers”. He explains that the gang normally aims at car windscreens: drivers who give chase often find radios or mobiles missing later. So much so normal in Hackney, Sinclair concludes, as he wipes the yolk out of his hair and reflects on life in the borough that has been his home for more than 30 years.

He admits a “shameful” ignorance about where he lives. The resulting investigation takes the form of a series of interviews with colourful locals, including barber-shop owners with stories about 1940s dockers’ strikes, solicitors with tales of council corruption in the 1980s (“housing officers were renting out council flats privately”), and doctors who remember when knife wounds were rare at Hackney Hospital (but staff drug-taking was not).

Sinclair has a fantasy “that everything and everybody can be found within 440 yards of my house”. In this respect, Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire is an anti-travel book: Sinclair simply strolling about absorbing “the novelty of street energies” along the way. No planes, trains or buses required. He clearly enjoys haunting the margins of the borough, avoiding egg-throwers and trouble as much as possible. Hackney, he honestly says, is “a game reserve for which you have to be very game; up to speed, cranked. Combat-hardened.”

While Sinclair may have an irritating bent for name-dropping (in particular that of his late friend J. G. Ballard) and a long-winded style, the picture that emerges is an intriguing insight into a fast-changing part of London.

Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire by Iain Sinclair (Penguin, £10.99, 592pp)

Viva South America! A Journey Through a Restless Continent by Oliver Balch

January, 2010

It may be 200 years since Simon Bolivar led the revolutionaries who overturned so much of the Old World colonial order in South America, but the spirit of revolution in the continent is alive and kicking. That is the premise upon which the journalist Oliver Balch embarked on a journey that took him from the southern reaches of Chile and Argentina to Colombia and Venezuela, Bolivar’s homeland, visiting nine countries along the way.

It may be 200 years since Simon Bolivar led the revolutionaries who overturned so much of the Old World colonial order in South America, but the spirit of revolution in the continent is alive and kicking. That is the premise upon which the journalist Oliver Balch embarked on a journey that took him from the southern reaches of Chile and Argentina to Colombia and Venezuela, Bolivar’s homeland, visiting nine countries along the way.

As he sets off in the footsteps of the Great Liberator on his year-long adventure, Balch says that although the “battle of ideas was supposed to have been buried with the Berlin Wall”, politics based on class divisions and a suspicion of “prowling robber barons in their midst” remains strong in South America. The continent, Balch believes, is angry, and he wants to find out why.

The result is an intriguing mixture of travelogue and reportage in which the author learns about illegal coca plantations and child miners in Bolivia, problems with Aids and the oppression of women in Chile, political disillusionment in Argentina, widespread corruption in Paraguay (“the most lawless corner of the continent”, where backhanders are a way of life), and “silent discrimination” and “racial apartheid” in Brazil, where Balch spends four nights living in a favela, dodging gangs and waking to the sound of gunshots. He learns of religious discord and falls ill from food poisoning on his trip to Machu Picchu in Peru (he drinks Inca Cola, “a bright-yellow fizzy drink that looks and tastes like radioactive waste”, to feel better), and goes hunting for spider monkeys (tastier than howler monkeys) with Huaorani hunters in Ecuador, many of whom have been displaced by multinational companies in search of fossil fuels.

In Colombia he talks to victims of drug barons, and encounters frustration with Hugo Ch?vez’s socialist revolution (and a lack of cash machines) in Venezuela, as well as El Comandante’s fondness for comparing himself with Bolivar, a national hero.

This is no guidebook for tourists, but for an insight into a continent still in flux — where the “crisp peel of greenbacks” appears to be all-important — Viva South America! delivers.

Viva South America! A Journey Through a Restless Continent by Oliver Balch (Faber and Faber, £9.99; 416pp)