by Tom Chesshyre

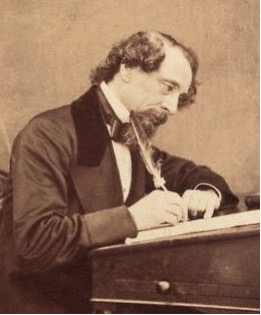

Charles Dickens had (very) itchy feet. He never seemed to stay still for long and probably clocked up as many miles as anyone during his 58 years — making voracious use of new railways and steamships, while writing about his wide-ranging adventures in letters and two travel books. Ever since he was a boy he had got about; thanks to his father’s work in the Navy Pay Office, which required the family to dart from Portsmouth, where he was born, to Chatham in Kent and then to London.

Charles Dickens had (very) itchy feet. He never seemed to stay still for long and probably clocked up as many miles as anyone during his 58 years — making voracious use of new railways and steamships, while writing about his wide-ranging adventures in letters and two travel books. Ever since he was a boy he had got about; thanks to his father’s work in the Navy Pay Office, which required the family to dart from Portsmouth, where he was born, to Chatham in Kent and then to London.

His wanderlust seemed to stem from there, and thanks to the success of his books, he soon had the cash to act on it — becoming perhaps the country’s first “tourist” (or at least one of the first), as we know them today.

Yes, there had been the dandies of the Grand Tour, who from around the 1660s onwards, blew their inherited money on seeing the sites in Italy. There was also Thomas Cook, who began his package tour holidays in 1841 with a train trip costing a shilling, taking temperance campaigners from Leicester to Loughborough. And then there were adventurers such as Livingstone, Burton and Speke exploring the deepest darkest reaches of Africa and the Middle East.

But Dickens had beaten Cook to it. He was already taking mini-breaks in the 1830s, and was not relying on family money like the grand tourists; he was paying his own way, picking and choosing where to go in the scattergun style that so many people do today. There can have been few people who pottered about abroad quite as much as he did, going on holiday after holiday (admittedly taking his writing work with him on many, if not most, of his trips).

He had a fabulous time . . . soon swapping breaks by the coast in Britain for sojourns to Italy, Switzerland and France — often taking the wife and kids — and transatlantic jollies to the United States. His attitude to travel seemed so blasé that during one three-year period he is believed to have crossed the Channel 68 times. He was not just leading the field with his writing, there can have been few travellers at the time who could have matched his mileage.

Dickens started simply with good old-fashioned seaside breaks — in reality, new-fangled holidays at the time, before the railways really brought British beaches to the masses. Broadstairs in Kent, not far from his childhood home in Chatham, was his favourite. He went for several summers with his family, first visiting in 1837 when The Pickwick Papers was almost complete. On one of his many visits, he took lodgings at 12 High Street and made friends with a kindly elderly woman named Mary Pearson, who lived nearby and sometimes gave him cake and tea; her house is now a Dickens Museum.

Pearson was slightly eccentric and could not abide donkeys passing in front of her property; later becoming the inspiration for Betsey Trotwood in David Copperfield, who famously had a similar aversion to mules. It’s clear that in Dickens case, travel did not just broaden the mind, it provided characters for his novels.

Before tackling North America, he tried out the Continent. He loved Italy. Dickens first visited in 1844, when he and his family travelled by coach to Marseilles — via a barge to Lyons — and then by sea to Genoa. The family took a grand villa and Dickens grew a moustache and enjoyed swimming in the sea. While there, he often went to operas at Teatro Carlo Felice. And after this mini-break, which he thoroughly enjoyed, he was soon back, producing an amusing travel book entitled Pictures from Italy.

He visited most major Italian cities including Milan, Rome, Florence, Pisa (where he went up the leaning tower) and Naples, from where he climbed Vesuvius in an extraordinary expedition with 22 guides in icy conditions. It was so dangerous that one of the guides slipped and died.

His description in his travel book of his trip to Verona, Mantua and Milan is gripping. He adores “pleasant Verona… with its beautiful old palaces”, but is stuck with a hilariously useless guide in Mantua, who seems to known nothing about the sights despite having presented himself as local expert. After a few moments consternation, Dickens decides to go with the flow and let the “guide” just wander round the streets, taking him any which way. Later on, he is taken to Milan by a coach driver who has to ask passersby the way. When he eventually arrives, he is unimpressed by Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, which he feels has been touched up by “bunglers”.

Dickens was not such a fan of Switzerland. In May 1846, he travelled with his wife and six children from Ramsgate to Ostend, along the Rhine to Strasbourg, and by train to Basle — to reach Lausanne. They spent six months there in Villa Rosemont at 14 Avenue Tissot. During their stay, he visited nearby Vevey and Chamonix, went to Geneva, entertained Tennyson (who was passing by), worked on Dombey and Son, and sorely missed his long night-walks in London. There was something about Lausanne that did not make him feel right (but that did not stop the authorities naming a street after him).

France was much more to his taste and he learnt to speak and write the language in remarkably quick time. He often visited Paris, where he stayed at the Hôtel Brighton and Hôtel Meurice, as well as Number 49 Champs Elysees. On one trip he met Victor Hugo, and enjoyed the city’s mixture of extravagance and beauty. “I cannot tell you what an immense impression Paris made upon me,” he wrote in a letter. “It is the most extraordinary place in the World! I was not prepared for, and really could not have believed in, its perfect direct and separate character. My eyes ached, and my head grew giddy, as novelty, novelty, novelty; nothing but strange and striking things came swarming before me.”

The Dickens family enjoyed long summer holidays in Boulogne-Sur-Mer between 1853 and 1856, while the author completed Hard Times and wrote parts of Little Dorrit. The resort replaced Broadstairs for his family breaks (he had ten children with his wife Catherine). He raved about the “piled and jumbled about” city, describing the “fishing people” and “their quarter of the town cobweb-hung with great brown nets across the narrow up-hill streets, they are as good as Naples every bit”.

In a letter to a friend, Dickens dramatically describes a rainstorm: “O the rain here yesterday! A great sea-fog rolling in, a strong wind blowing, and the rain coming down in torrents all day long.”

Dickens stayed at a house overlooking the ramparts and enjoyed clifftop walks, on one occasion spotting Prince Albert and Napoleon III, who were surveying troops. In later years, Dickens often visited the nearby village of Condette, where he met up with his lover Ellen Ternan.

Dickens took two long trips to North America. In his travel book American Notes, he brilliantly captures his 1842 passage from Liverpool, where he’d stayed at the Adelphi Hotel (enjoying a splendid parting meal of turtle, cold punch, hock, claret and champagne on his final night in Britain). Half way across a storm struck, and Dickens describes a water jug in his cabin “plunging and leaping like a lively dolphin”. Then he is confined to bed. “I lay there all day long, quite coolly and contentedly with no sense of weariness, with no desire to get up, or get better, or take the air; with no curiosity, or care, or regret, of any sort or degree, saving that I think I can remember, in this universal indifference, having a kind of lazy joy.”

After a brief stop in Halifax, Novia Scotia, where passengers indulged in oysters and champagne, the ship sailed onwards: “The indescribable interest with which I strained my eyes, as the first patches of American soil peeped like molehills from the green sea, and followed them, as they swelled, by slow and almost imperceptible degrees, into a continuous line of coast, can hardly be exaggerated.”

His two tours of North America took Dickens far and wide. In the States, Dickens met Longfellow in Boston, where he complained of “infernally hot” rooms, visited lunatic asylums in New York (Dickens enjoyed his own style of tourism), met Edgar Allan Poe in Philadelphia and President Andrew Johnson in Washington DC. He went onwards through mountains to St Louis, describing the Mississippi as the “beastliest river in the world”. He also considered Ohio to be “morose”.

Of the people, he said that Americans were “friendly, frank, kind and warm-hearted”, although he disliked their habit of spitting tobacco. He also believed Americans showed insecurity in their “constant appetite for praise”.

On his first American trip, Dickens and his wife spent ten days by Niagara Falls on their way to Toronto. When he arrived at the waterfalls, he saw “two great white clouds rising up from the depths of the earth”. And at the water’s edge, he was amazed by the “bright rainbow at my feet”.

And all of this was on top of his UK holidaymaking. Dickens went just about everywhere in the UK, becoming perhaps the country’s best passenger in the early days of rail. He visited Ireland and Scotland (he was given the freedom of the City of Edinburgh). He regularly enjoyed trips to Birmingham and Manchester, where he made many book readings. He is said to have based Hard Times on Preston after a visit.

He rowed from Oxford to Reading describing the journey as “more charming than I can describe in words. I rowed down last June, through miles upon miles of water-lilies, lying on the water close together, like a fairy pavement”. On another mini-break, he swam from Petersham to Richmond Bridge one morning for a bit of exercise (to the astonishment of all around). He adored galloping across the Salisbury Plains, but was attacked by a horse in Brighton. But he wasn’t afraid to criticise — complaining once that Norwich was boring, although Chelmsford was “the dullest and most stupid place on earth”.

His favourite place in the UK was around Chatham (where he lived until aged ten) and the Kent marshes, which had left such an impression on him that he drew upon the landscape in the famous opening of Great Expectations: “(There was) a dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dykes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it… the low leaden line beyond was the river… the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing, was the sea.”

Dickens bought Gad’s Hill, a house just north-west of Chatham, when he was successful; it was there that he died in 1870. Over the years, he walked for miles through the Medway area, sometimes crossing 30 miles into London. He believed that the seven miles from Rochester to Maidstone was “one of the most beautiful walks in England”.

In short, Dickens got about — a lot. He enjoyed his jaunts; they seemed to reinvigorate him. Was he Britain’s first real “tourist”? Maybe. He sure did like a holiday.

DICKENS ON THE MOVE

Charles Dickens on Travel (Hesperus, £7.99), Dickens on France: Fiction, Journalism and Travel Writing by John Edmondson (Signal Books, £16.99), Pictures from Italy by Charles Dickens (Penguin, £11.99), American Notes: For General Circulation by Charles Dickens (Penguin, £9.99), Dickens’s England by Tony Lynch (Batsford, £14.99), Charles Dickens: A Life by Clare Tomalin (Viking, £30).